The Beginner’s Guide to Data Science Experimental Design:

Now that we’ve looked

at the different types of data science questions, we are going to spend some

time looking at experimental design concepts, in our last lesson of our first Course "The Data Science Toolbox" in our Data Science Specialization using R Programming. As a data scientist, you are

a scientist and as such, need to have the ability to design

proper experiments to best answer your data science questions!

What does experimental design mean?

Experimental design is

organizing an experiment so that you have the correct data (and enough of it!)

to clearly and effectively answer your data science question. This process

involves clearly formulating your question in advance of any data collection,

designing the best set-up possible to gather the data to answer your question,

identifying problems or sources of error in your design, and only then,

collecting the appropriate data.

Why should you care?

Going into an

analysis, you need to have a plan in advance of what you are going to do and

how you are going to analyze the data. If you do the wrong analysis, you can

come to the wrong conclusions!

We’ve seen many

examples of this exact scenario play out in the scientific community over the

years - there’s an entire website, Retraction Watch, dedicated to identifying papers that have

been retracted, or removed from the literature, as a result of poor scientific

practices. And sometimes, those poor practices are a result of poor

experimental design and analysis.

Occasionally, these

erroneous conclusions can have sweeping effects; particularly in the field of

human health.

For example, here we have a paper that was trying to predict the effects of

a person’s genome on their response to different chemotherapies, to guide which

patient receives which drugs to best treat their cancer. As you can see, this

paper was retracted, over 4 years after it was initially published. In that

time, this data, which was later shown to have numerous problems in their

set-up and cleaning, was cited in nearly 450 other papers that may have used

these erroneous results to bolster their own research plans. On top of this,

this wrongly analyzed data was used in clinical trials to determine cancer

patient treatment plans. When the stakes are this high, experimental design is

paramount.

Principles of experimental design

There are a lot of

concepts and terms inherent to experimental design. Let’s go over some of these

now!

Independent variable

(AKA factor): The variable

that the experimenter manipulates; it does not depend on other variables being

measured. Often displayed on the x-axis.

Dependent variable: The variable that is expected to change

as a result of changes in the independent variable. Often displayed on the

y-axis, so that changes in X, the independent variable, effect changes in Y.

So, when you are

designing an experiment, you have to decide what variables you will measure,

and which you will manipulate to effect changes in other measured variables.

Additionally, you must develop your hypothesis, essentially an

educated guess as to the relationship between your variables and the outcome of

your experiment.

Let’s do an example

experiment now! Let’s say for example that I have a hypothesis that as shoe

size increases, literacy also increases. In this case, designing my experiment,

I would choose a measure of literacy (e.g.: reading fluency) as my variable

that depends on an individual’s shoe size.

To answer this

question, I will design an experiment in which I measure the shoe size and

literacy level of 100 individuals. Sample size is the number

of experimental subjects you will include in your experiment. There are ways to

pick an optimal sample size, that you will cover in later courses. Before I

collect my data though, I need to consider if there are problems with this

experiment that might cause an erroneous result. In this case, my experiment

may be fatally flawed by a confounder.

Confounder: An extraneous variable that may affect

the relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

In our example, since

age affects foot size and literacy is affected by age, if we see any

relationship between shoe size and literacy, the relationship may actually be

due to age – age is “confounding” our experimental design!

To control for

this, we can make sure we also measure the age of each individual so that we

can take into account the effects of age on literacy, as well. Another way we could control for

age’s effect on literacy would be to fix the age of all

participants. If everyone we study is the same age, then we have removed the

possible effect of age on literacy.

In other experimental

design paradigms, a control group may be appropriate. This is

when you have a group of experimental subjects that are not manipulated.

So if you were studying the effect of a drug on survival, you would have a

group that received the drug (treatment) and a group that did not (control).

This way, you can compare the effects of the drug in the treatment versus

control group.

In these study

designs, there are other strategies we can use to control for confounding

effects. One, we can blind the subjects to their assigned

treatment group. Sometimes, when a subject knows that they are in the treatment

group (e.g.: receiving the experimental drug), they can feel better, not from the

drug itself, but from knowing they are receiving treatment. This is known as

the placebo effect. To combat this, often participants are blinded

to the treatment group they are in; this is usually achieved by giving the

control group a mock treatment (e.g.: given a sugar pill they are told is the

drug). In this way, if the placebo effect is causing a problem with your

experiment, both groups should experience it equally.

And this strategy is

at the heart of many of these studies; spreading any possible confounding

effects equally across the groups being compared. For example, if you think age

is a possible confounding effect, making sure that both groups have similar

ages and age ranges will help to mitigate any effect age may be having on your

dependent variable - the effect of age is equal between your two groups.

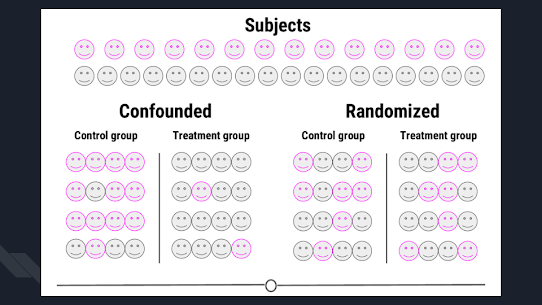

This “balancing” of

confounders is often achieved by randomization. Generally, we don’t

know what will be a confounder beforehand; to help lessen the risk of

accidentally biasing one group to be enriched for a confounder, you can

randomly assign individuals to each of your groups. This means that any

potential confounding variables should be distributed between each group

roughly equally, to help eliminate/reduce systematic errors.

Randomizing subjects

to either the control or treatment group is a great strategy to reduce

confounders’ effects

Randomizing subjects

to either the control or treatment group is a great strategy to reduce

confounders’ effectsThere is one final

concept of experimental design that we need to cover in this lesson, and that

is replication. Replication is pretty much what it sounds like,

repeating an experiment with different experimental subjects. A single

experiment’s results may have occurred by chance; a confounder was unevenly

distributed across your groups, there was a systematic error in the data

collection, there were some outliers, etc. However, if you can repeat the

experiment and collect a whole new set of data and still come

to the same conclusion, your study is much stronger. Also at the heart of

replication is that it allows you to measure the variability of

your data more accurately, which allows you to better assess whether any

differences you see in your data are significant.

Sharing data

Once you’ve collected

and analyzed your data, one of the next steps of being a good citizen scientist

is to share your data and code for analysis. Now that you have a GitHub account

and we’ve shown you how to keep your version controlled data and analyses on

GitHub, this is a great place to share your code!

In fact, hosted on

GitHub, the Leek group, has developed a guide that has great advice

for how to best share data! Check it out.

Beware p-hacking!

One of the many things

often reported in experiments is a value called the p-value. This

is a value that tells you the probability that the results of your experiment

were observed by chance. This is a very important concept in statistics that we

will be covering in depth in our Statistical Inference course, if you want to

know more, check out this video explaining more about p-values.

What you need to look

out for is when you manipulate p-values towards your own end. Often, when your

p-value is less than 0.05 (in other words, there is a 5 percent chance that the

differences you saw were observed by chance), a result is considered significant. But if you do 20 tests, by chance, you would

expect one of the twenty (5%) to be significant. In the age of big data,

testing twenty hypotheses is a very easy proposition. And this is where the

term p-hacking comes from: This is when you exhaustively search a data

set to find patterns and correlations that appear statistically significant by

virtue of the sheer number of tests you have performed. These spurious

correlations can be reported as significant and if you perform enough tests,

you can find a data set and analysis that will show you what you wanted to see.

Check out this FiveThirtyEight activity where you can manipulate and

filter data and perform a series of tests such that you can get the data to

find whatever relationship you want! Check it out.

XKCD mocks this concept in a comic testing

the link between jelly beans and acne - clearly there is no link there, but if

you test enough jelly bean colors, eventually, one of them will be correlated

with acne at p-value < 0.05!

Summary

In this lesson we covered what experimental design is and why good experimental design matters. We then looked in depth to the principles of experimental design and defined some of the common terms you need to consider when designing an experiment. Next, we detoured a bit to see how you should share your data and code for analysis. And finally, we looked at the dangers of p-hacking and manipulating data to achieve significance.

Comments

Post a Comment

Type your comment here.

However, Comments for this blog are held for moderation before they are published to blog.

Thanks!